Organic textiles

Ensuring a more sustainable model for the environment, workers, and consumers.

The current conventional textile production, processing, and business model are highly unsustainable. Organic textiles, with their benefits both at the raw material and at the processing level, aim to counteract the massive negative environmental and social impacts of the global textile sector.

The fashion sector is contributing “directly and significantly to the triple planetary crisis of climate change, nature and biodiversity loss, and pollution and waste (UNEP 2021c; UNEP 2023). Currently, it is considered responsible for between 2% and 8% of global greenhouse gas emissions, as well as significant pollution, water extraction and biodiversity impacts, not to mention social injustices worldwide (UNEP 2023).”

Organic textiles are textiles such as clothes, accessories and home textiles, but also materials such as yarns or fabrics, that have been certified under an organic textiles standard. Organic textiles contain a high amount of certified organic natural fibres, which can be of plant origin, such as cotton, hemp or flax, or animal origin, such as wool or silk. They all have in common that the raw materials are produced on organic farms and according to the same high standards as organic food crops.

The organic raw materials are then further processed into organic textiles in facilities that are certified to fulfill high environmental and social standards, making sure to protect textile workers and nature alike. In short, the principles of organic – ecology, health, fairness, and care – are at the heart of organically-produced textiles.

Find out more about organic textiles:

https://global-standard.org/the-standard/gots-key-features

https://www.soilassociation.org/take-action/organic-living/fashion-textiles

For the past 20 years, humanity has been producing more and more clothes, with a shorter and shorter life cycle. A considerable proportion of them become waste and are not recycled. Our planet cannot sustain this in the long-term.

Overproduction is largely attributed to polyester textiles made from fossil fuels. These textiles are not sustainable, they cause a massive waste problem, and release microplastics into the environment.

Natural fibres from conventional farms are also associated with a higher negative environmental impact than raw materials produced on organic farms. One example is cotton production. The numbers are concerning: conventional cotton production uses around 6% of the world’s pesticides and 16% of the world’s insecticides. It also releases a considerable amount of manufactured nitrogen fertilisers into the environment – approximately 83% of the total. It is also estimated that pesticides poison 77 million textile workers every year.

“Natural” only tells us that the fiber is made from plants or comes from an animal – unlike synthetic fibers such as polyester, that is made from petroleum. The term “natural” says nothing about HOW this plant was grown, or HOW the animal was living.

The term “organic”, conveniently, gives us this information: an organic crop, such as cotton or hemp, is grown without the use of synthetic pesticides and fertilisers, and respecting organic production standards. Organic animals, such as sheep or goats, live better – they have access to grazing areas and are treated with respect for their welfare. Another example is wool. Certain practices related to wool production, such as mulesing of sheep, are considered cruelty against animals and are not allowed in organic.

Organic textiles address these problems in various ways. They use natural raw materials from organic farms that are produced with respect for the environment, farm workers and farm animal welfare. Organic farming bans hazardous pesticides, transgenic techniques, and synthetic fertilisers. Organic textiles use environmental and social sustainability standards in textile processing.

For more information about the social and environmental impact of textile production, as well as the impact of greenwashing on the sector, please check our document “Social & environmental impacts of organic and non-organic textiles – An overview of the literature“.

Worldwide, 21 countries are growing organic cotton, the three main ones are India, China, and Kyrgyzstan. According to the 2021 Organic Cotton Market Report, 249,153 tonnes of organic cotton were produced in 2020, a figure that is in constant growth – the production is expected to expand by 48% in 2021. As the market develops, organic cotton becomes a more attractive option for farmers.

Learn more about organic cotton:

https://www.fibl.org/de/shop/1391-cotton-toolkit

https://organiccottonaccelerator.org/

https://www.fibl.org/en/shop-en/1185-participatory-cotton-breeding

Greenwashing means that false or misleading claims are made about how environmentally friendly a product is, and it is an enormous problem in the sector. Consumers are misled into believing that they buy sustainable products, by qualifications such as “green”, “conscious”, or even “recycled”. These terms suggest that a textile product is sustainable, without giving any proof or substantiation of this claim. Over 80% of EU citizens agree that not enough information is available on the clothes they buy, and stricter rules are necessary.

Currently, unlike organic agri-food products, the term “organic textiles” is not protected and regulated at the EU level. This creates an opportunity for brands and retailers to make false claims about their products’ sustainable and organic nature.

IFOAM Organics Europe advocates for the protection of organic textiles under a legal framework, such as the textiles regulation. Organic textiles should of course be certified by an accredited and independent certification body. Only textiles that are truly sustainable should be labelled as organic.

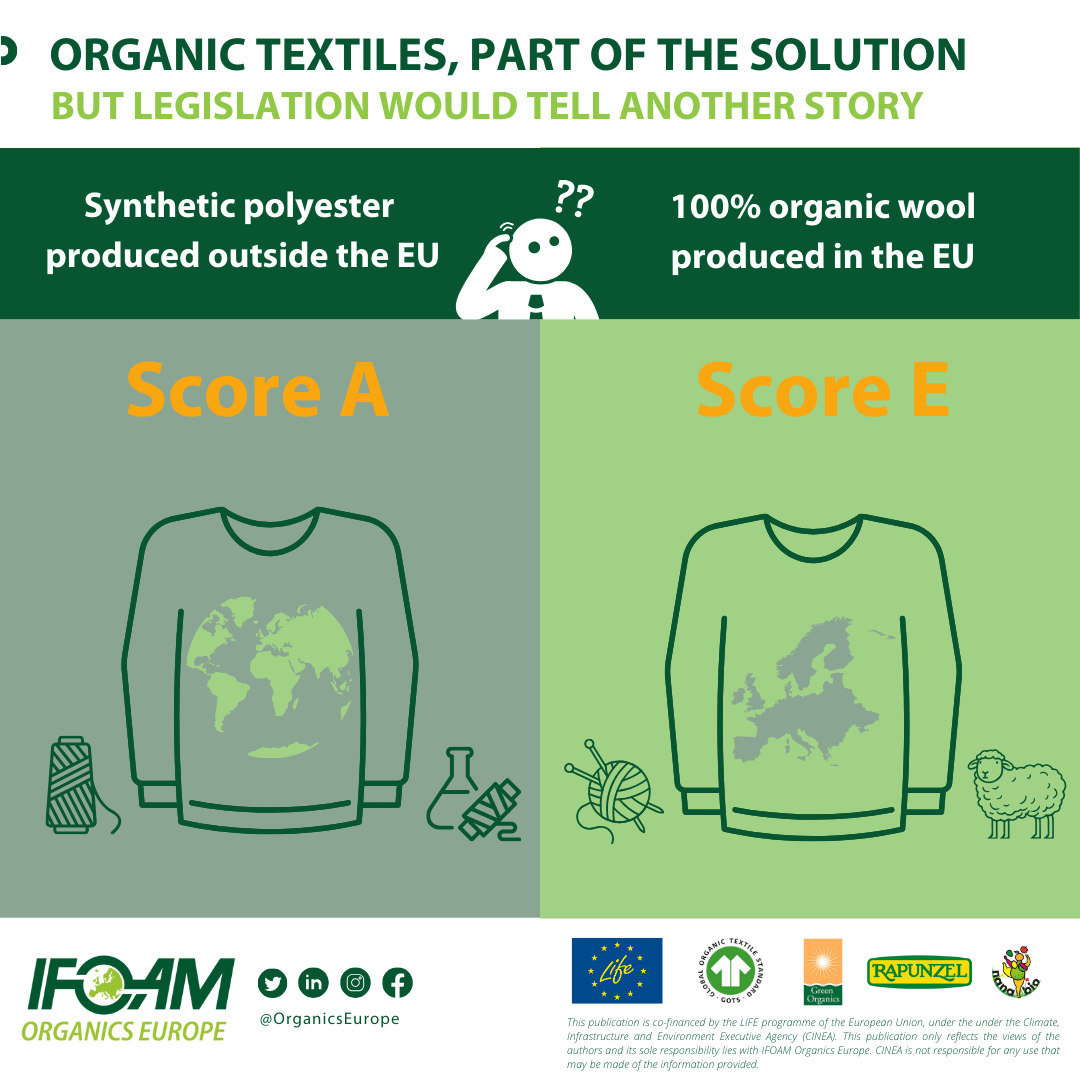

Another specific greenwashing risk in the textile sector is related to methods that assess how eco-friendly a product is. Using flawed methods, for example to compare polyester and natural fibre textiles, will lead to results that actually favour synthetic textiles over natural fibre textiles. If the comparison methods do not take into account microplastic release, plastic waste and use of fossile fuels for synthetic fibres, but instead focus on the land use (which is higher for natural fibers sourced from farmed materials), the consequence will be that natural fibres score lower than synthetic fibres in sustainability rankings.

IFOAM Organics Europe:

- Advocates for organic farming and the use of certified organic natural fibres;

- Advocates for an EU-legislation on organic textiles addressing the disparity of legal regimes between textiles and agri-food products and protecting the credibility of the EU organic label;

- Recommends including the term ‘organic’ in the EU Textile Regulation (1007/2011), specifying the conditions for using the term in relation to textile products. On this, IFOAM – Organics International recommends that this label relates to the entire production and processing chain, as is the case for certified organic food and drink products;

- Unites the most relevant actors in organic textiles to create a common position and defend these interests in an organic textile taskforce;

- Contributes to advocacy activities in the field of textiles, and related topics like consumer protection, a shift to more sustainable products, and the fight against false claims.

Legislative background

In the European Union, Regulation (EU) 1007/2011 on fibre names and related labelling and marking of the fibre composition of textile product regulates the way textiles placed on the European market are designed and labelled. Its main provisions are the obligation to state, among others, the full fibre composition of a product, and minimum technical requirements for applications for a new fibre name. This regulation covers all products containing at least 80% textile fibres, including raw, semi-worked, worked, semi-manufactured, semi-made, and made-up products. The EU Strategy for sustainable textiles foresees to reopen this regulation.

The Regulation (EU) 2018/848 on organic production and labelling of organic products establishes a new regulatory framework for organic production that also explicitly covers products such as cotton, wool, and silk worms that were not addressed in previous regulations (art. 2).

Ongoing processes

The Circular Economy Action Plan, that sprung from the 2019 European Green Deal, identified the textile sector as one to be made more circular. Several initiatives are resulting from this:

- Sectorial policies,

- The Sustainable Products Initiative,

- The Substantiating Green Claims Initiative, and

- The Empowering Consumers in the Green Transition Initiative.

IFOAM Organics Europe will contribute to the policymaking debate and respond to public consultations.

EU strategy for sustainable textiles

In March 2022, the European Commission published the EU Strategy for sustainable textiles. It aims at acting holistically on production, product design, consumption, traceability, transparency, and end of use. IFOAM Organics Europe would have liked to see mention of organic textiles, given their high degree of coherence with the strategy’s rationale and objectives. We are looking forward to the reopening of the Textile Labelling Regulation as foreseen by the strategy.

Sustainable products initiative

The Commission published the Sustainable products initiative in the first quarter of 2022. This initiative does not solely target textiles, but they are part of its scope. Moreover, it should tackle important issues, such as the presence of chemicals, thresholds on durability, reusability, repairability, recyclability, environmental and social requirements, responsibility of producers for providing more circular products. In June 2024, the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR) was adopted as the larger part of the Sustainable Products Initiative. Textiles (garment and footwear) are amongst the prioritised product groups for which the EU Commission will propose regulation on detailed ecodesign requirements.

Strengthening the role of consumers in the green transition

The Empowering Consumers in the Green Transition initiative was also presented during the first quarter of 2022. It ensures that consumers get reliable and useful information on products, especially to prevent overstated environmental information (‘greenwashing’). It also aims to regulate the use of misleading words such as “eco, green, conscious.”

Initiative on substantiating green claims

Finally, the Substantiating Green Claims initiative is expected for the first quarter of 2023 and would tie into the legislative proposal on empowering consumers in the green transition. It will require companies to substantiate any sustainability and impact claim.

This initiative considers the Product Environmental Footprint (PEF) methodology, which is based on a life cycle analysis (LCA) to assess a products’ impact on the environment. Meaningful and balanced environmental and social information of textile products is essential. However, the PEF has various shortcomings, and cannot be the sole methodology to underpin this information. This holds true for agri-food products, as this joint letter by a coalition of environmental NGOs explains, and also for textile products.

While the product-focused PEF serves well to compare manufactured industrial goods, the approach significantly lags when evaluating the environmental performance of complex agricultural systems, including natural fibre production, in a holistic way. When applied to agriculturally derived natural products, such as cotton, wool, hemp, jute, kenaf, and flax, the PEF gives misleading results in which synthetic and industrial fibre production score better. In other words, the PEF favours intensive, industrial textile production instead of extensive, natural agricultural practices and has no eye for both the positive and negative external costs of the production process. Among other things, the PEF does not account for the impacts of production systems on biodiversity and the use of pesticides, and does not have an indicator on microplastic emissions and end-of-life practices.

IFOAM Organics Europe is active on the topic of PEF in relation to textiles and has co-signed an open letter to the European Commission to criticize the standalone application of the methodology in the textile and apparel industry.

The work of IFOAM Organics Europe on this topic is co-financed by the LIFE programme of the European Union, under the Climate, Infrastructure and Environment Executive Agency (CINEA). This page only reflects the views of the authors, and its sole responsibility lies with IFOAM Organics Europe. The CINEA is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information provided.

The work of IFOAM Organics Europe on this topic is co-financed by the Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS). This page only reflects the views of the authors, and its sole responsibility lies with IFOAM Organics Europe. GOTS is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information provided.